Bolivia’s second-largest lake dries up due to climate change

People that have been living off its waters for generations, now become refugees

People that have been living off its waters for generations, now become refugees

Lake Poopó is situated 12,140 feet above sea level in the dry Bolivian high plains, in the area of Llapallapani. Decades of water diversion and cyclical El Niño droughts had brought it to the brink many times over the years. But climate change was the finishing blow. The lake warmed 0.23 °C (0.41 °F) on average each decade since 1985. The fish went extinct in 2014 and the lake basically disappeared last December, when the little water left evaporated (due to slow warming).

The vanishing of Lake Poopó threatens the very identity of the Uru-Murato people, the oldest indigenous group in the area, who had lived off its waters for generations. They survived through the conquests of the Inca and the Spanish, but seem unable to adjust to the abrupt upheaval climate change has caused. “The lake was our mother and our father,” said Adrián Quispe, one of five brothers who were working as fishermen and raising families here in Llapallapani. “Without this lake, where do we go?” The lake had offered even more to the local people, as the algae called huirahuira was used to relieve coughs and the flamingos living by the lake also provided numerous remedies: their pink fat was used to relieve rheumatism and the feathers to fight fevers when burned and inhaled. Only 636 Uru-Murato are estimated to still remain in Llapallapani and two nearby villages. Since the fish died off in 2014, people had left to work in lead mines or salt flats up to 200 miles away, and those who stayed behind have begun growing quinoa instead.

Milton Pérez, an ecologist at Oruro Technical University, said scientists had known for decades that Lake Poopó fits the profile of what he called a dying lake. But the prognosis was for the distant future, no one expecting such a rapid decline. “We accepted the lake was going to die someday,” he said. “Now wasn’t its time.” He kept watching with alarm the several threatening trends that developed, and began to understand that the lake could evaporate for good. First, as quinoa became popular abroad, booming production of the grain diverted water upstream, lowering Lake Poopó’s level. Second, mining sediment was quickly silting the lake from below. And it was also the rising temperatures, which had increased on the plateau by 0.9 °C (1.6 °F) from 1995 to 2005 alone, much faster than Bolivia’s national average. “We had the possibility that all these factors would hit with a synergy never seen before,” Mr. Pérez said.

Lake Poopó is one of several lakes worldwide that are vanishing because of human causes. California’s Mono Lake and Salton Sea were both diminished by water diversions; lakes in Canada and Mongolia are jeopardized by rising temperatures.

Former fishermen have begun growing quinoa instead, and others left to work in salt flats

Source: New York Times

Source: New York Times

Want to read more like this story?

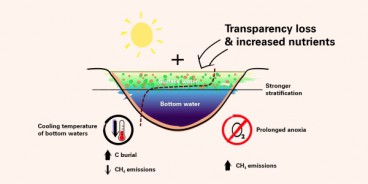

The surprising effect of greenhouse gas in lakes

Sep, 16, 2019 | NewsAccording to a new study, the effects of greenhouse gases are different than anticipated in lakes....

4 lakes in mid-Michigan, disappeared after dam failure, are being restored

Oct, 25, 2022 | NewsFour dams are being restored after catastrophic failures led to four man-made lakes disappearing in...

The debate on decommissioning the Glen Canyon Dam at the Colorado River

May, 25, 2016 | NewsThere are signs that this great dam has proved less efficient than originally planned There...

[Video]: Watch Lost Lake Disappear!

Apr, 23, 2015 | NewsWatch this video of Oregon’s aptly named Lost Lake disappear! Every spring, Lost Lake turns in...

The Lake That Was Born From An Earthquake

Sep, 14, 2015 | NewsDespite the tempting turquoise waters, the story behind this beautiful lake is worrying. The Sarez L...

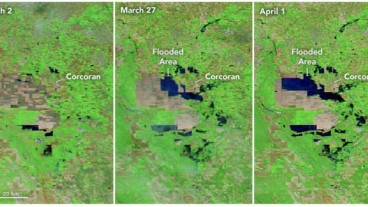

California’s Tulare “ghost” lake reemerges

Mar, 21, 2023 | NewsCalifornia’s Tulare Lake, a “ghost” lake that was dried up during the late 19th and early 20th cent...

Liquid Petroleum Gas to Blame in Drinking Water Salinity?

Mar, 01, 2015 | NewsA recent report links high salinity in Seneca Lake, the largest of New York State’s Finger Lak...

Dam in Buckeye Lake to be replaced

Mar, 23, 2015 | NewsOhio governor committed to rebuild the Buckeye Lake dam to adress the significant flooding ris...

60-foot crack appears on rural Utah Panguitch Lake Dam

Apr, 08, 2024 | NewsA 60-foot-wide and 2 to 5-foot-tall crack was identified at rural Utah’s Panguitch Lake Dam, on the...

Trending

Vertical gardens in Mexico City to combat pollution

Characteristics of Load Bearing Masonry Construction

Taipei 101’s impressive tuned mass damper

Saudi Park Closed After 360 Big Pendulum Ride Crashes to Ground, 23 injured

Dutch greenhouses have revolutionized modern farming

Federal court rules Biden’s offshore drilling ban unlawful